One could say it was fate that brought Hans Knoll and Jens Risom together. Born on the same day, May 8th, two years apart, the two would meet shortly after emigrating to the United States from Germany and Denmark in 1937 and 1938, respectively.

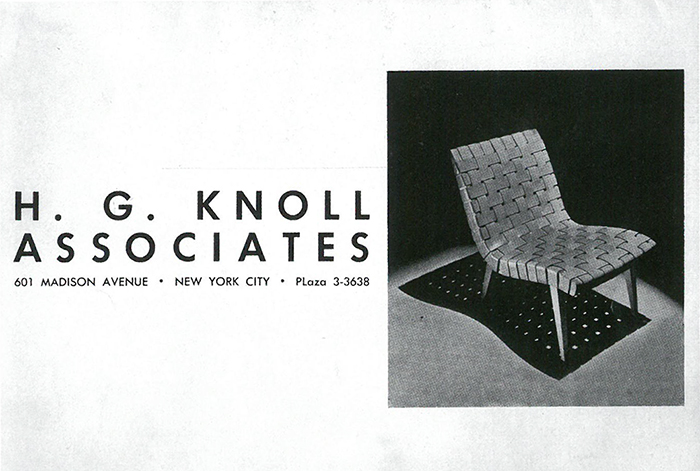

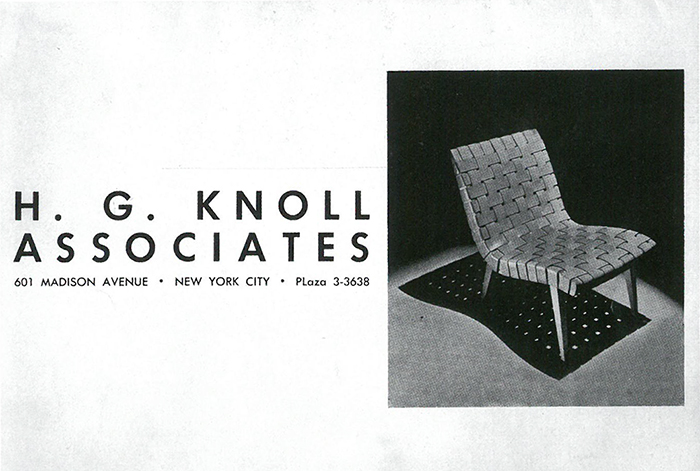

Original Hans G. Knoll Associates advertisement with the 650 Line Lounge Chair designed by Jens Risom. Image from the Knoll Archive.

“The minute the 650 Line was out there, it was a success. It sold. That chair got us through the war.”

—Helen Risom

Hans Knoll was just months into a brand-new business venture, a furniture company then-called Hans G. Knoll Associates. In spite of grand ambitions, Knoll’s product inventory was lackluster, made up of a few pieces imported from Sweden, which floundered in the American market, and some unexceptional designs from Michigan. Knowing that the war would disrupt his supply lines in Europe, Hans Knoll was searching for someone to develop an original line of in-house furniture to replace the nondescript designs he was working with at the time.

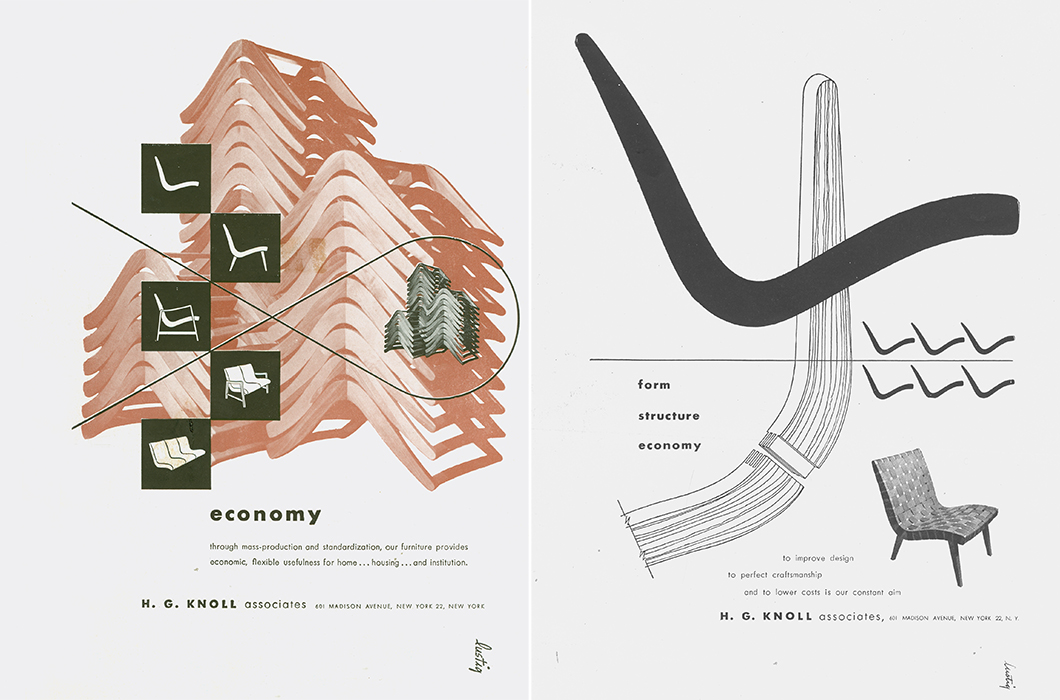

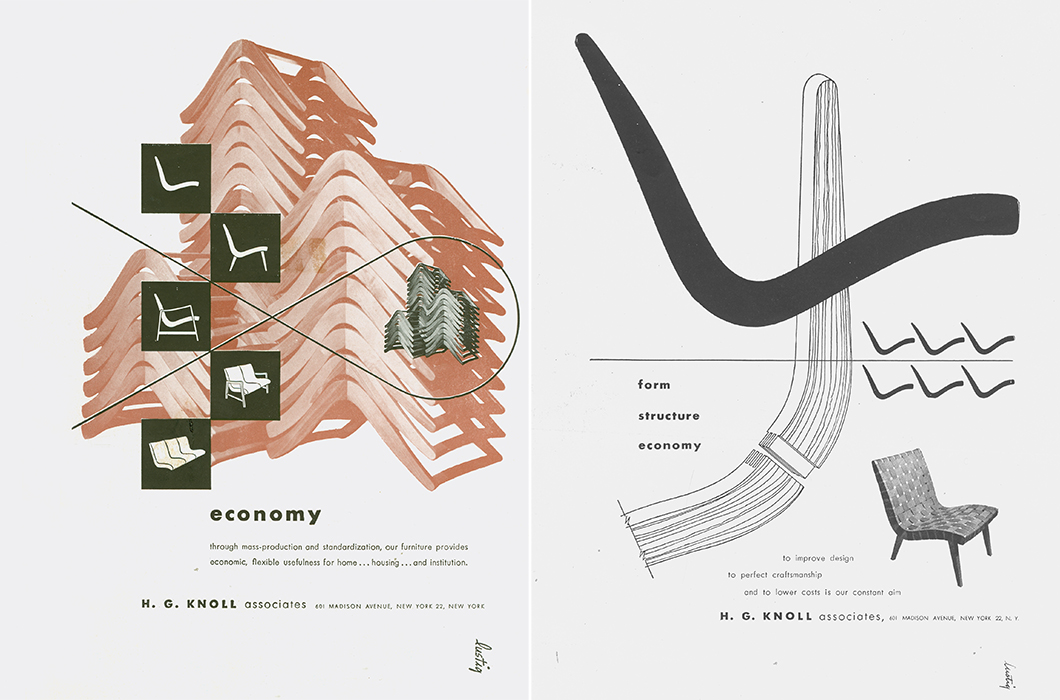

Original advertisements for the Jens Risom 650 Series designed by Alvin Lustig, c. 1944-1945. Images from the Knoll Archive.

Jens Risom was experiencing a similar level of success. Although formally trained as a woodworker in Denmark, Risom had come to America to see what the country had to offer in the way of contemporary furniture designs. "He was appalled to find there was nothing," his daughter, Helen Risom, told Knoll. As a result, he was having difficulty finding work and was searching for a champion and salesman of his own furniture.

“All the architects were thirsty for good design that wasn’t Chippendale.”

—Helen Risom

An early Knoll showroom featuring the 650 Line Lounge Chair and an early Florence Knoll stacking stool. Image from the Knoll Archive.

Luckily, Knoll and Risom found each other. In 1941, the two young men, just 27 and 26, prepared to embark on a research road trip around the country. ”It was Knoll's idea to make a tour of the United States,” writes Brian Lutz in Knoll: A Modernist Universe, “to assess the interests and needs of interior architects, in order that his furniture address real American needs.“ With his in-house designer in toe, Hans Knoll mapped the itinerary, beginning with Tennessee, Dallas and California. "Off we went," Risom remembered, "in a brand-new Plymouth convertible, a two-door job.

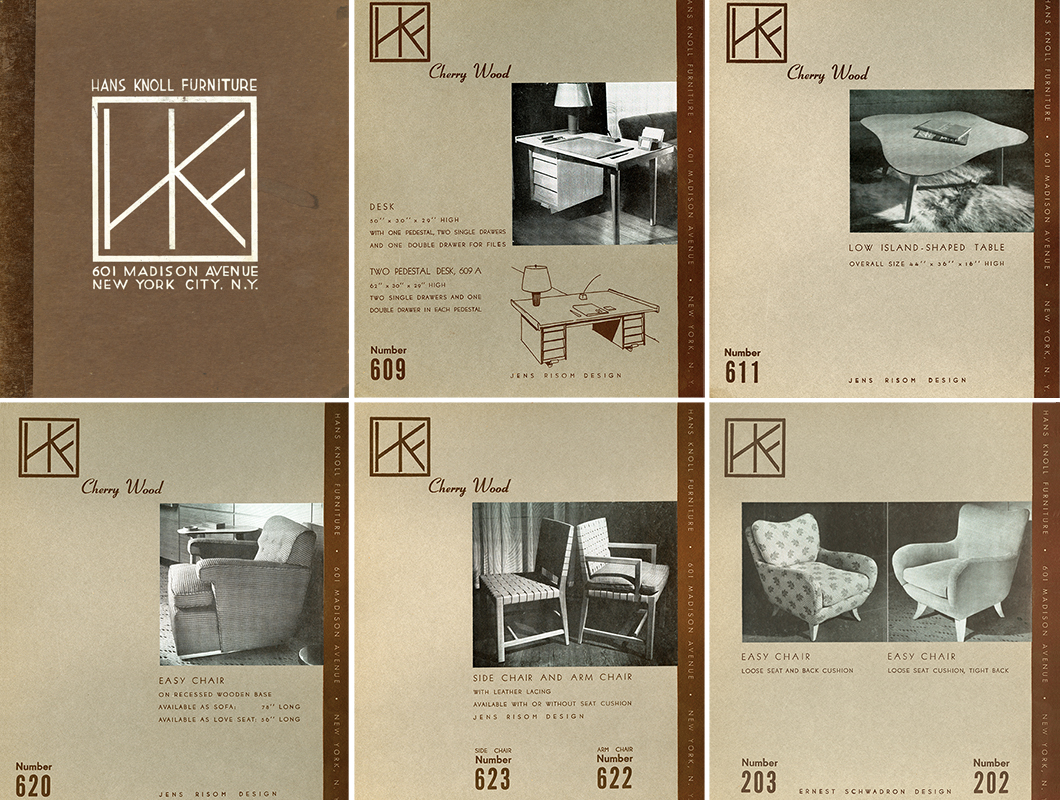

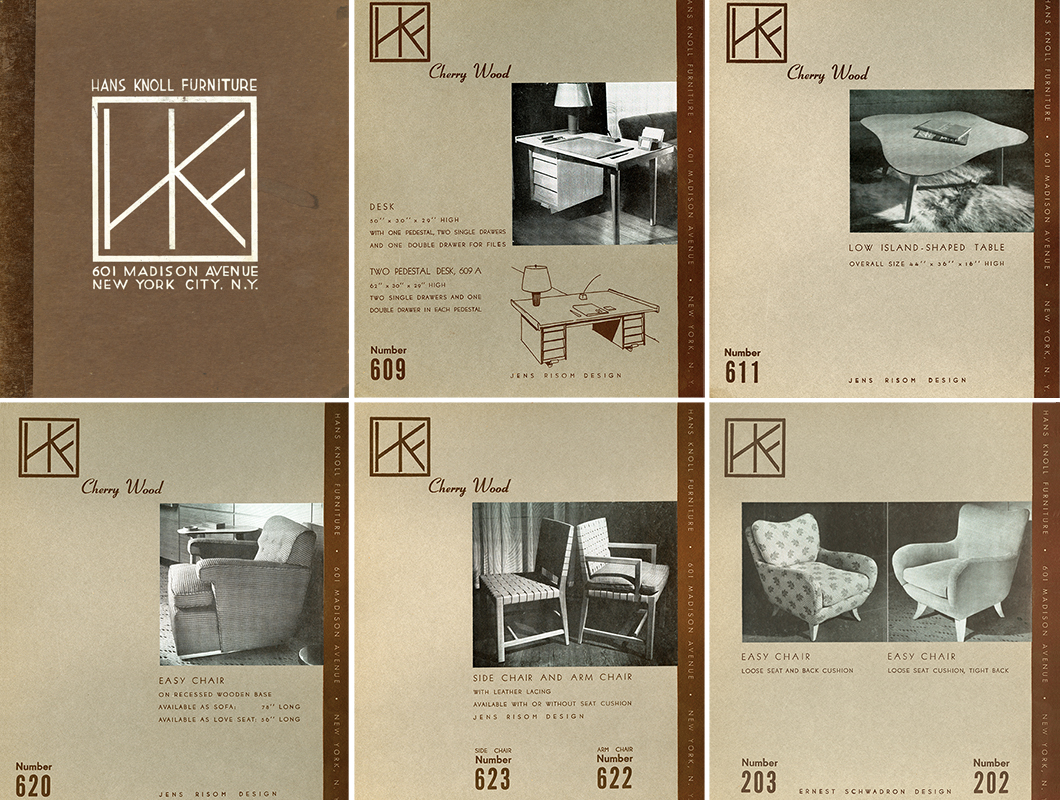

The original product catalogue for Hans G. Knoll Associates designed by Hans Knoll and Jens Risom, c. 1942. Image from the Knoll Archive.

Eric Larrabee, author of Knoll Design, wrote of the journey: “They began [their] four-month tour around the United States with their wives [by] talking to architects and designers; Howard Meyers [editor and publisher of Architectural Forum] gave them names of the ones to see, some of whom later became good Knoll customers. There was then more contemporary work to be had in the West and Southwest than in the East, but they nonetheless decided that New York City was the center of design and the place for them.”

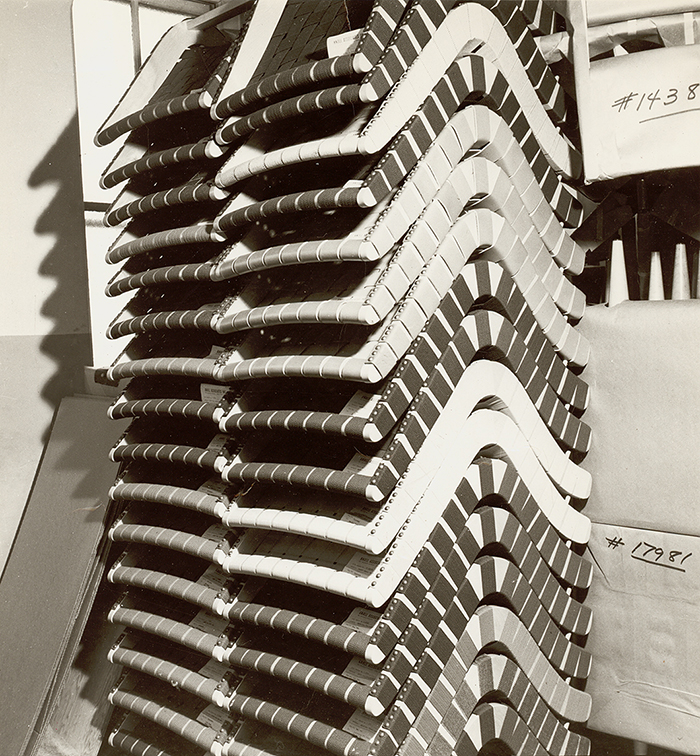

“The 650 Line was intended for project use during wartime. We could only use non-critical materials for production, such as parachute straps that had been rejected by the military.”

—Jens Risom

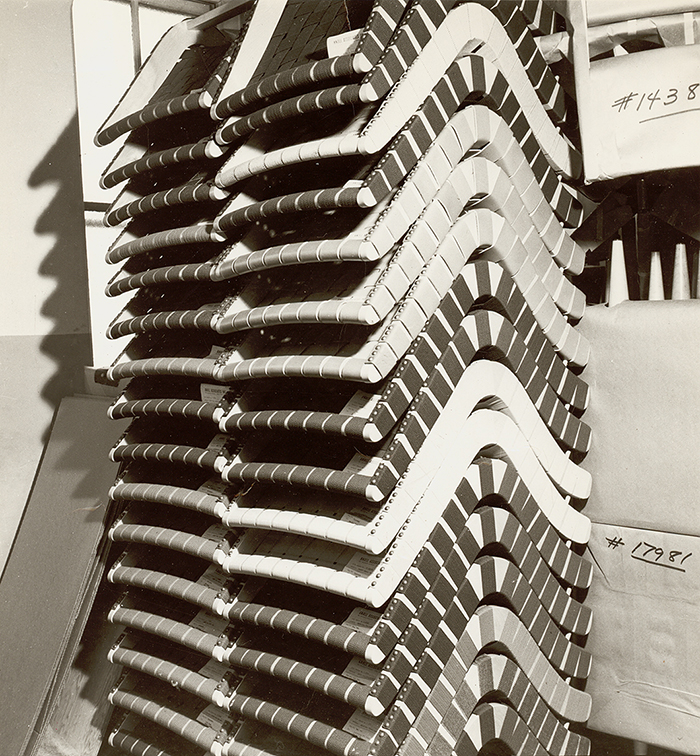

Stacks of Jens Risom's 650 Line Lounge Chairs. Image from the Knoll Archive.

Having arrived back in New York with a renewed sense of purpose, the two got to work on the company’s first catalogue, a group of twenty-six 8 x 10 inch cards. Of the twenty-five pieces in the first catalogue, published in August 1942, fifteen were conceived and designed by Jens Risom after the findings of their trip. The designs were made out of cherry, which Risom preferred to the more common light woods, like maple and birch, he found to be “too clinical.” Named "600 Series," this initial selection did not yet include Risom’s most well-known designs.

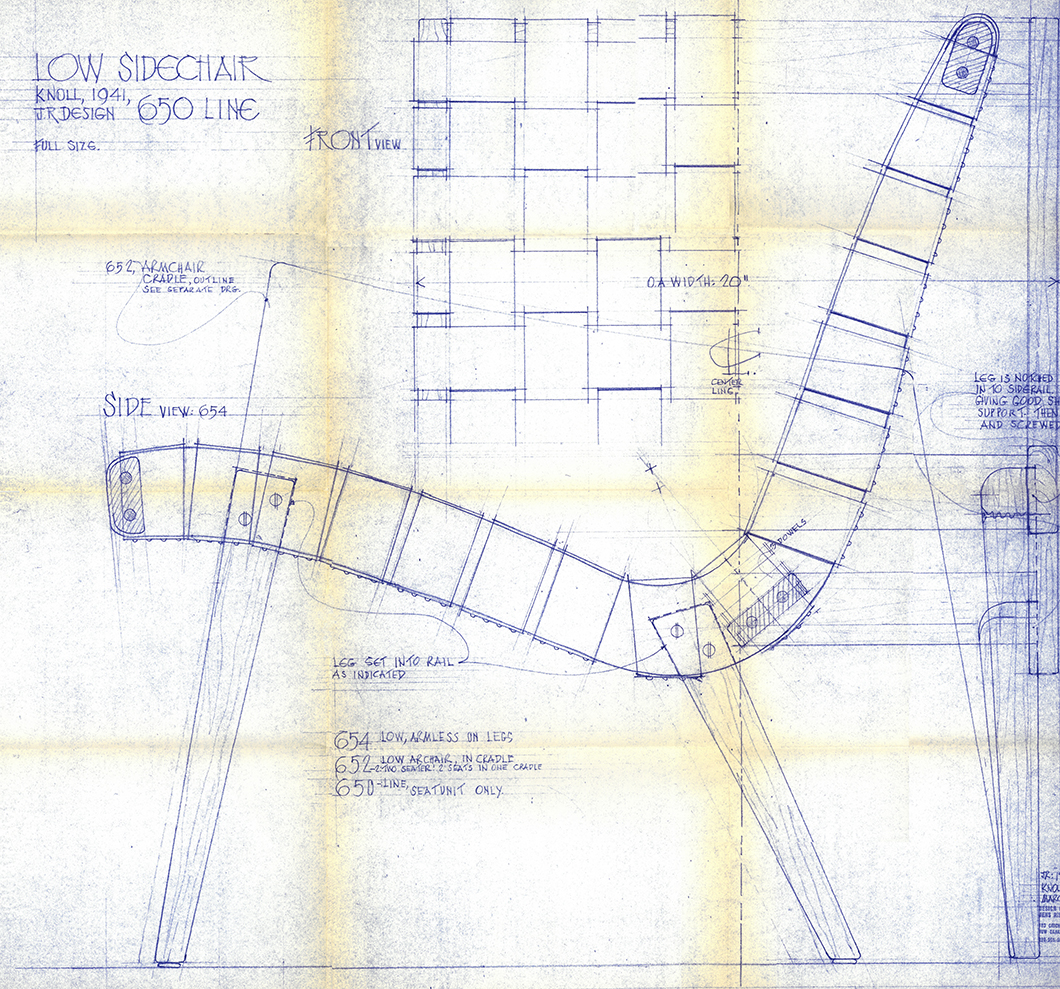

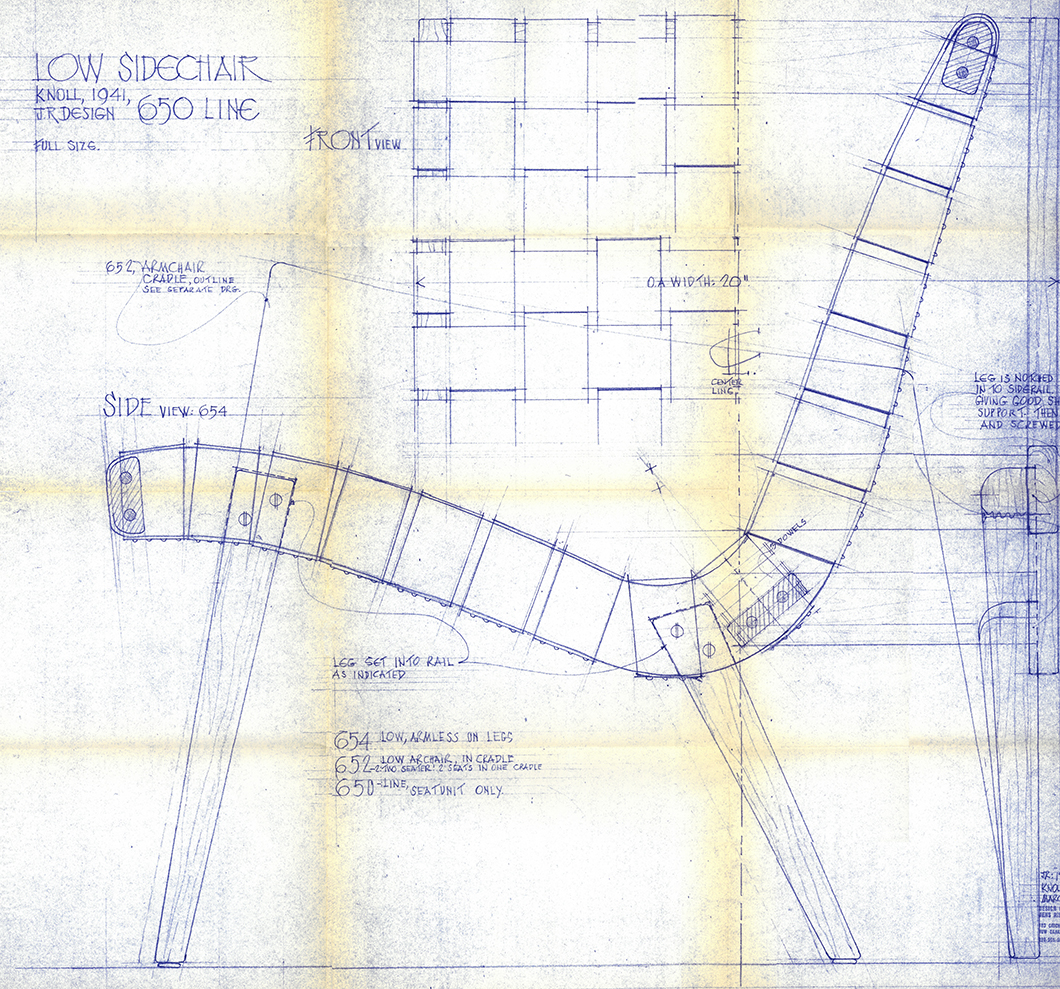

Blueprint for the 650 Line Lounge Chair designed by Jens Risom, c. 1943. Image from the Knoll Archive.

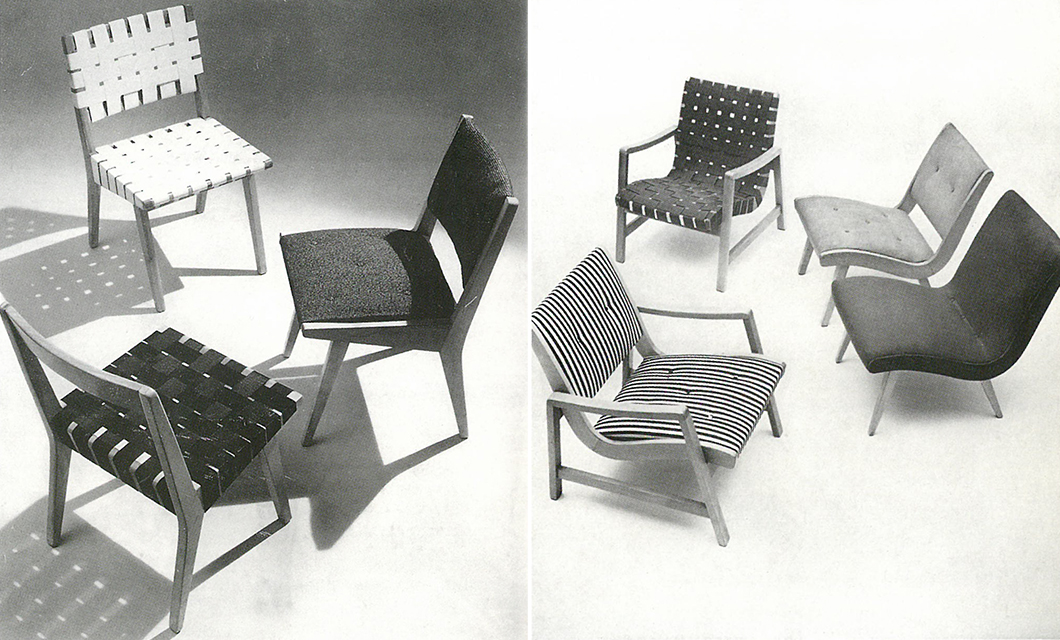

Facing increasingly stringent wartime rationing, within three months Hans Knoll was forced to change tack. He put Risom to work on more spartan designs, which became collectively referred to as the 650 Line. Risom recalled, “The 650 Line was intended for project use during wartime. We could only use non-critical materials for production, such as parachute straps that had been rejected by the military.’ Upon release, Risom’s collection would be among the only modern furniture available. Deliberately designed for a wartime market, the collection was simple in construction and inexpensive to produce. Of the lot, the Side Chair and Lounge Chair enjoyed particular success. “All the architects were thirsty for good design that wasn’t Chippendale," Helen Risom explained of the chairs’ popularity, "The minute he was out there, it was a success, it sold, it was an instant hit. That chair got us through the war.” Jens Risom later recalled that the line was “bought for a lot of lounges: USO lounges, company lounges, airports, almost anything.”

“Prefabricated furniture is the latest output of a streamlined manufacturing system born of war. Standardized parts arrive, unassembled, at the purchaser's home, and may be put together immediately without benefit of screws or nails.”

—Mary Madison

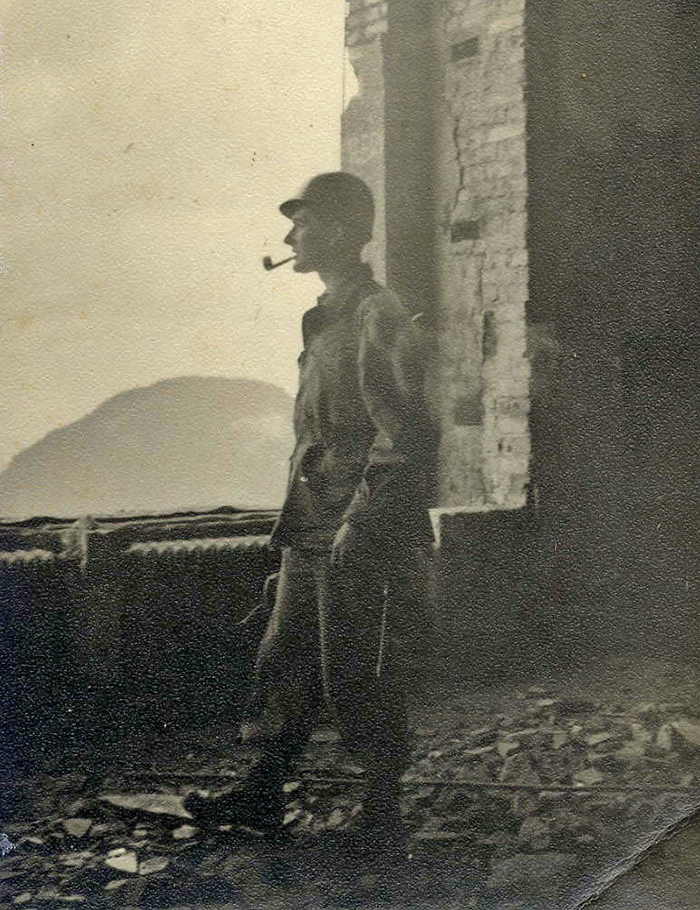

Jens Risom as a soldier during WWII, 1943. Image courtesy of Jens Risom.

On July 18, 1943 The New York Times took note. In a column entitled, "The Home in Wartime," Mary Madison wrote up the trend brought on by the introduction of the 650 Line: "Prefabricated furniture is the latest output of a streamlined manufacturing system born of war. Standardized parts—arms, legs, spine-fitting seats and backs—are as indefinitely interchangeable as the pieces of a child”s mechano set. They arrive, unassembled, at the purchaser's home, and may be put together immediately without benefit of screws or nails. Chairs and settees (consisting simply of a larger frame and two or three of the standard seat units) are done in lattice-woven webbing—bark-brown, green, tile-gray and olive-drab—and also in rough-textured upholstery fabrics, canvas and even occasionally in non-priority leather."

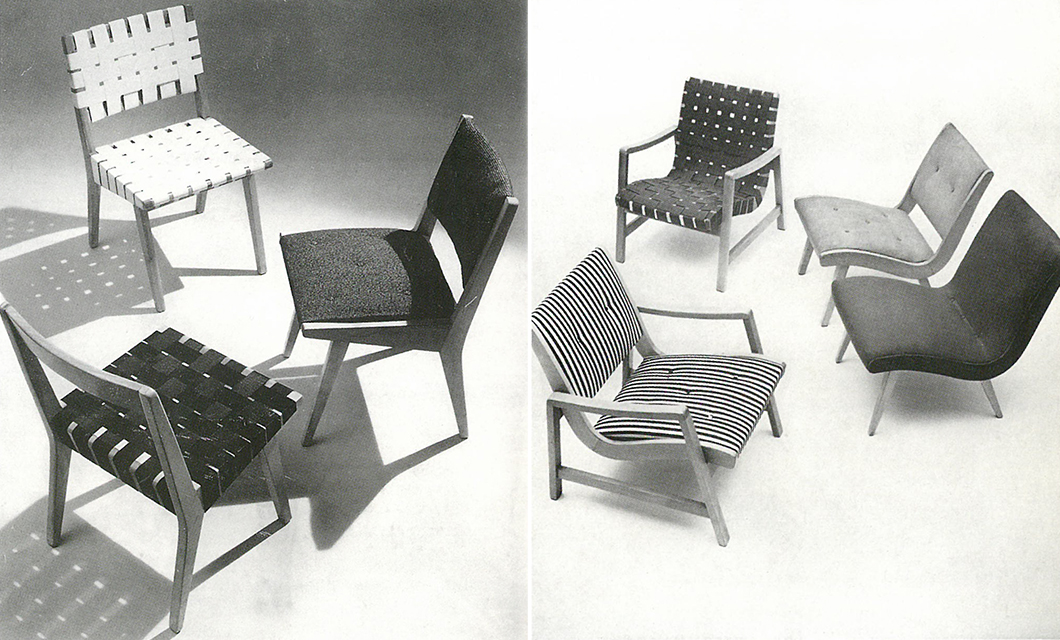

Left: The 666 Side Chair designed by Jens Risom, c. 1943. Right: The 650 Line designed by Jens Risom, c, 1943. Images from the Knoll Archive.

In the remaining months before Risom was drafted into the army in August 1943, the duo collaborated on other projects: two interiors at the New York World’s Fair; a press lounge at the General Motors exhibit; Norman bel Geddes’s popular Futurama; and, finally, the “living kitchen” of the “America at Home” booth designed by Allmon Fordyce. Risom also designed the first Knoll showroom at 601 Madison Avenue, later re-designed by Florence Knoll.

“The Answer is Risom.”

—Advertisement, c. 1950s

Risom Side Chairs. Photography by Ilan Rubin.

After returning from the war in 1946, Risom worked briefly with Knoll before establishing his own furniture line: Jens Risom Design. The company’s tagline was, appropriately, “The Answer is Risom.”

Discover The Risom Collection

All images are from the Knoll Archive or courtesy of Jens Risom unless otherwise noted.