An Artist in Abiquiú

Georgia O'Keeffe calls home a "faraway" place

Georgia O’Keeffe is among the most well-known American artists of the 20th century, while remaining widely misunderstood. In spite of the notoriety garnered for the sexual imagery of her famous Calla Lily paintings—which fetched the highest price for a group of paintings by a living American artist when they were first shown—O’Keeffe’s primary concern has always been modernism. “She was completely committed to perpetuating modernism,” says Carolyn Kastner, Curator at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe.

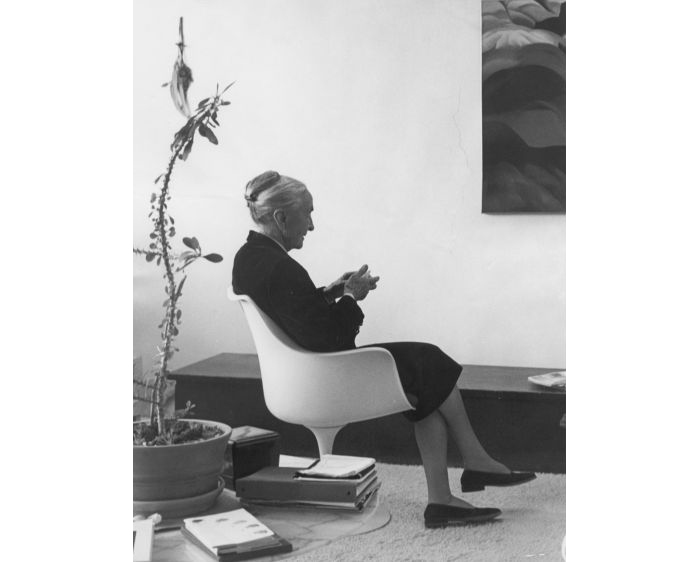

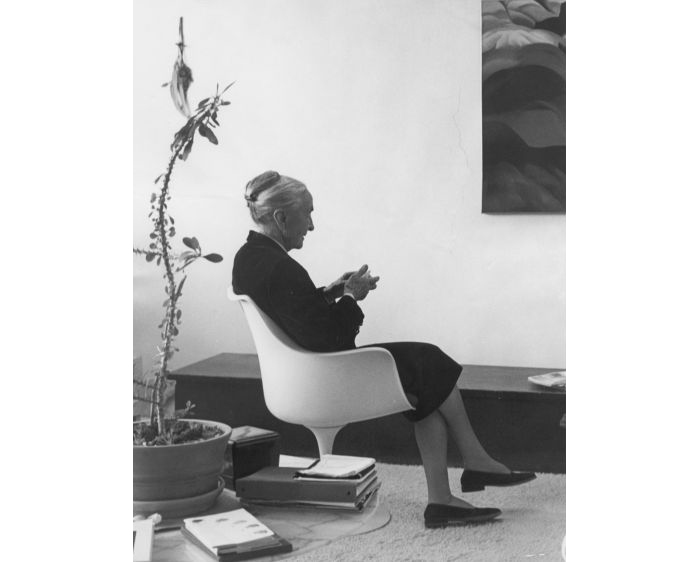

Georgia O'Keeffe seated in a Tulip Armless Chair at Juan Hamilton's Studio, 1981.

Photograph © Todd Webb. Courtesy of Evans Gallery and the Estate of Todd & Lucille Webb.

Among the first American painters to make the leap into abstraction, O’Keeffe’s career is a testament to both her talent and persistence. Living in a time when women were barred from many schools, O’Keeffe managed to attain an education at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), the University of Virginia and the Teachers College of Columbia University—which, as a woman, she was only able to attend during summer sessions. It was there that she learned the theories of Arthur Wesley Dow, an influential arts educator whose ideas had a profound impact on her methodology. “I had a technique with my materials,” O’Keeffe said of Dow, “but he gave me something to do with it.” In the intermittent years, she experimented with a variety of different media—including charcoal drawing, watercolors and oil painting—all in pursuit of a new, modern vocabulary.

“I had a technique with my materials, but he gave me something to do with it.”

—Georgia O'Keeffe

Left: Calla Lily Turned Away, 1923 by Georgia O'Keeffe, pastel on paper-faced cardboard. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

Right: From The River — Pale, 1959 by Georgia O'Keeffe, oil on canvas. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

It should come as no surprise, then, that her two homes in Abiquiú, New Mexico display a similar preoccupation with modernism and modern design. “She had training in design at SAIC,” Kastner explains, “and I think that really honed her skills at looking and making a dramatic gesture.” While records do not reveal dates of purchase, photographs as late as 1960 show the full collection of her furnishings. Since O’Keeffe bought the two properties in 1940 and 1945, respectively, one can only assume they were furnished in the intervening decades, coinciding with the release dates for emblematic pieces of modern design—the Hardoy Chair (1947), the Saarinen Coffee Table (1948) and the Bertoia Bird Chair (1952). “The timeline adds up, and it makes sense,” says Kastner, “but we just don’t know.” The museum is still looking to establish that she was, in fact, an early adopter.

Womb Chair, Womb Ottoman and Barcelona® Table in Georgia O'Keeffe's sitting room in Abiquiú, New Mexico.

Photograph by Herb Lotz, 2007. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

Regardless of the precise date of acquisition, furniture like Mies’ Barcelona® Table and Saarinen's Womb Chair has formed a “continuous part of the living room, remaining among its most permanent fixtures.” Purposefully positioned over two adobe structures that O’Keeffe designed—since replaced with pouffes—the Barcelona® Table and its glass top afforded a glimpse of the Navajo textiles O’Keeffe draped over the mounds, appropriating Mies’ design for her own ends. “There’s a consistent aesthetic that is apparent in her artwork, in the way she lives and in the way she looks at this furniture,” explains Kastner. “This is what Arthur Wesley Dow meant to her. He taught her how to fill a space in a beautiful way.”

Bertoia Bird Chair and Saarinen Coffee Table in Georgia O'Keeffe's studio in Abiquiú, New Mexico.

Photograph by Herb Lotz, 2007. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

When O’Keeffe lived in New York, her Shelton residence—which she shared with her husband, the eminent photographer Alfred Stieglitz—was sparsely furnished, though the furniture she did own was laden with black dust covers. Similarly, in Abiquiú, her furniture was draped in white linen slipcovers, which remained unhemmed and untrimmed. “From the beginning of its life,” says Kastner of one of O’Keeffe’s chairs, “this chair was covered. She loved its design and its comfort, but she never gave the light of day to the upholstery.” This black-and-white dichotomy carries over to other aspects of O’Keeffe’s life, including her wardrobe. “Although she wore brilliantly colored, patterned clothing—reds, plaids, stripes, checks, even one dress with tiny tulips on it—when photographed, she’s always shown wearing black and white. The furniture just follows suit.” Even the sites that she frequented offer stark contrast. Two such locations were “Black Place,” an outcrop 150 miles west of her Ghost Ranch in the Bisti Badlands, and “White Place,” a rock formation behind her Abiquiú home. “Both of these sites form part of this incredible landscape of the American Southwest,” says Kastner, “and what interested her was the drama, [calcified] in the exposed rock.”

“I like to think of her homes as two of her greatest works of art.”

—Carolyn Kastner

Georgia O'Keeffe's house in Abiquiú, New Mexico. Photograph by Herb Lotz, 2007. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

A collector of stones, bones and debris, O’Keeffe gathered these natural artifacts from the desert and incorporated them amidst her décor, reinforcing her visual vocabulary. As Kastner explains, “She was always taking things and making them fit within her idea of an aesthetic field.” A window sill covered with rocks of all shapes and sizes testifies to this penchant for collecting. Some of these accrued objects found their way onto her canvases, like the ram's head, which she painted again and again, making her home an extension of her artistic process. “I like to think of her homes as two of her greatest works of art,” concludes Kastner. “She was always editing, demonstrating that there was nothing beyond her control.”

Project Credits:

Photography: Todd Webb

All images are courtesy of the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum unless otherwise noted.